"The moral nihilism of celebrity culture is played out on reality television shows, most of which encourage a dark voyeurism into other people's humiliation, pain, weakness, and betrayal."

-Chris Hedges

Last week I was contacted by the producer of an upcoming documentary on the rise and fall of Girls Gone Wild. He called mostly looking for off the record background, as near as I can tell, but we fell into an hourlong meander through anecdotes about those days that weren't publicly known, for the most part. He told me early in the call that the theme they'd sought to develop centered upon how jarring the sexism and exploitation of that moment seems in looking back through the lens of the subsequent #metoo movement. I'm not sure how an interview with me on camera would fit into all that, but he's called back to inquire whether I'd be willing to do it.

I have mixed feelings about talking about those days in a public forum. On the one hand, I've endured some calumny from Joe Francis's inner circle, published by a newspaper reporter who wrote a book about the whole saga that he hoped would lift him out of journalistic penury. He never asked me about my side of the story, and the book never sold. Karma can be a bitch. It would be nice to set the record straight on some things.

On the other hand, there is the ethical tightrope of maintaining client confidentiality, a continuing obligation even after the representation terminates, while telling the story. Confidential information could be woven into the res gestae of the picture the interview creates, and crossing the line could mean an ethics violation. Not good.

I also wonder about dredging up what Wordsworth called those "Old, unhappy, far off things, and battles long ago." Those few weeks nearly broke me; I quit law and went to teach a few months later, hoping to get the stench out of my clothes and my soul. I can laugh about it now, all just a bad movie in my head. What happens when I bring that demon back to life?

What are my motivations? I mean my real motivations?

The whole situation has me looking back at other celebrity encounters I've had in the twenty-seven years I've been doing this. Don't think a small town lawyer from the panhandle deals with the famous and nearly famous? You'd be surprised.

My first experience sharing space with the, well, infamous, came when I found myself in Judge Cole's chambers up in Chipley, making small talk with Jim Bakker, of Jim and Tammy Faye and the whole PTL debacle.

It was maybe 2000, and I represented a bank that was in the midst of foreclosing on a metal building in Washington County that had been owned by an electrical parts supplier. Apparently Bakker thought the Sunny Hills area would be a great spot to restart his media career after his fall from grace, and this cavernous warehouse had the potential to serve as his studio.

It's not an uncommon thing for folks who've done very bad things to move to Florida for a fresh start. Back then the internet was just coming into being as we know it, and a person could vanish from the moral or ethical tragedy they were living in Atlanta or Charlotte, and reappear in Panama City as a new person with a mostly made up resume, only to fall, usually, into the same degraded behavior that got them there. They brought themselves along, after all.

I don't remember what Bakker and I talked about. It seems to me the conversation centered on how tough it was back then to get to the panhandle, and what drew him to this foreclosure proceeding. I was there with my friend and now condo neighbor Russell, the special assets guy for a now-defunct bank, and didn't want to come off as too starstruck at this diminutive, smooth talking fellow with his combover teased into a George Jones pompadour.

We didn't sell Bakker the building. I think it sat vacant for years, "REO" in the parlance of banking, a thing the bank really wanted to sell but which presented a limited buyer pool with its size and remote location. No clue why Bakker didn't buy it.

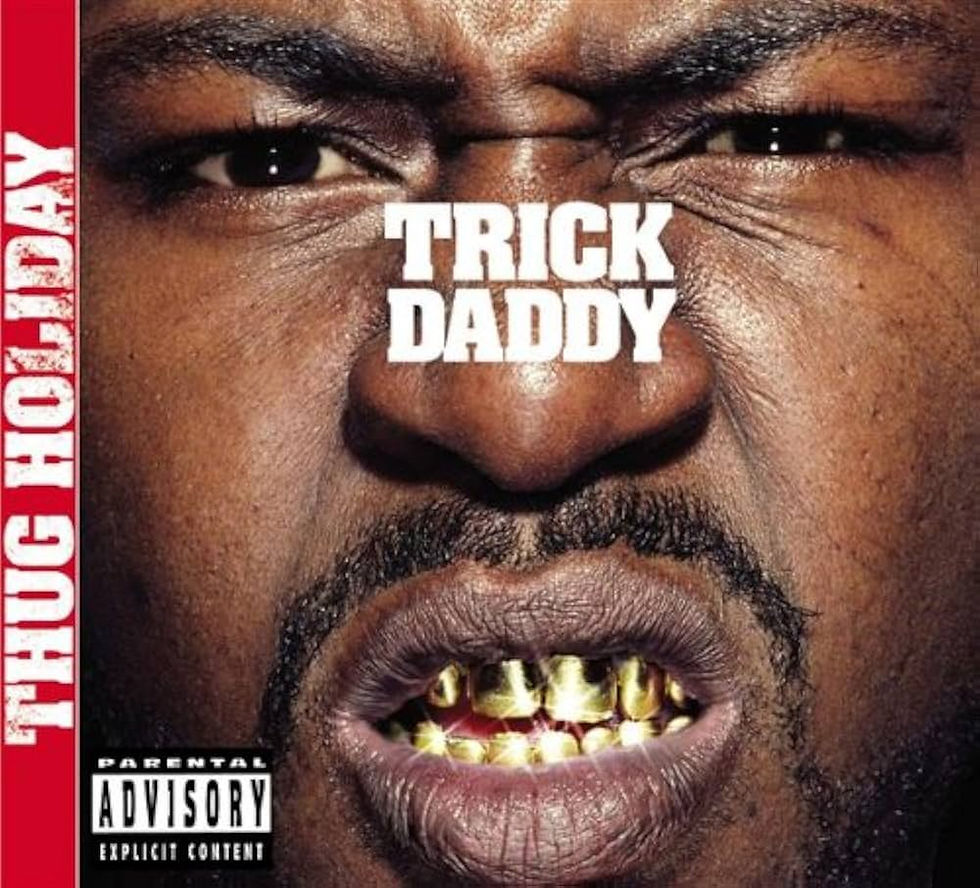

A couple years later I was called by a lawyer down in Broward County about representing his client, a rapper known as Trick Daddy. Apparently Trick had been sued in Bay County for ghosting a concert at Spinnaker, once an iconic beach club. Sparky the owner at Spinnaker claimed Trick had been served with suit papers as he was leaving the Marina Civic Center with his entourage months later, never filed an answer, and was now on the wrong end of a default final judgment Sparky was trying to collect. Trick claimed he'd never been served.

We filed a motion to set aside the default based on defective service, which in turn required an evidentiary hearing in front of my friend Mike Overstreet, then a circuit judge. On the appointed day the client arrived for his hearing, surrounded by an entourage of very serious black handlers that looked like the walking embodiment of Morehouse Men, in their pressed khakis and polo shirts. Trick took my suggestion of wearing a collared shirt, but it was huge and untucked.

I started into my spiel about what to expect at the hearing when the entourage cleared the room to run some sort of errands around town. In the paneled conference room adorned with fox hunting prints, the client looked me in the eye.

"You don't know who I am, do you?"

In fact I did not, at least until my eldest son, a huge fan of the rapper, directed me to Trick's webpage, at www.thug.com.

Same guy. Same gold grill.

"I'm a big deal. No way somebody think they served me when they didn't."

I told him I'd take his word for it.

Later we walked up McKenzie Avenue to the courthouse. As we crossed the parking lot, a well-worn Corolla stopped abruptly, and two young ladies fell out of the doors on each side.

"Trick! Trick! Is that you? Oh, I want you Trick! I want to have your baby!"

Trick turned to me, open palmed and head cocked as if to say, "See. I told you so."

We won the hearing. In true Southern fashion, my friend the process server, a retired cop, admitted that he might be wrong about whom he served, and that he had a little trouble telling those people apart. The judge complimented him for his candor, and granted our motion. The case later settled.

Years later, during the pandemic, I received a call from a friend who, through a series of contacts, was asked to find legal representation for Jeff Cook, the lead guitarist of the bank Alabama.

Jeff had advanced Parkinson's, and with the band about to go on tour without him a disagreement had arisen regarding his entitlement to a third of the net proceeds, per the terms of their longtime agreement, when obviously his health would prevent him from performing most nights. The other two band members were threatening to boycott and call off the tour if a different arrangement wasn't reached.

I agreed to take the representation, against my better judgment because it would involve flying to Nashville in the middle of Covid, and driving down to Fort Payne, Alabama, where the three of them had lived since they were children.

Jeff and his wife lived in a home they'd designed themselves, Cook Castle, where to this day you can hold a wedding reception and some such.

I stayed there that night, and the two of them were incredibly gracious about opening up their home, showing me lots of gold records on the walls (those are actually a thing) and other memorabilia from the heyday of the band. We ate Chinese takeout and watched reruns; it was downright domestic. Jeff was in pretty bad shape, but all there and upbeat despite the inevitable. He'd written a song called No Bad Days around the time he was diagnosed, and seemed to be living the message.

When the morning came to meet with the band I was sent down alone from the Castle to the conference room of the Alabama Fan Club and Museum in Fort Payne, where the other two members and the band's longtime lawyer waited in a small conference room.

It was sort of a sad spot, filled with memorabilia of another time and place for all of us, made sadder because, to the extent it was ever busy, Covid left the place feeling hollow and vacant.

When I arrived, the band's lead singer, Randy Owens, sat at the head of the table and seemed to be in charge. Teddy Gentry looked uncomfortable sitting off to the side. The lawyer, whose name I'll leave out, had represented the band since they were playing honky tonks in Myrtle Beach four decades ago, and since had gone on to represent the likes of Taylor Swift. He was a face card in Nashville, but also a nice guy, a very savvy negotiator, and obviously this was a bit of a trip down memory lane for him.

Hours of negotiation ensued, with Randy playing chess with me over terms, Teddy periodically bursting up from his chair to let me know how unfair it was for Jeff to expect to be paid while they busted their asses on the road, and the lawyer trying to be the umpire, which is about all he could do given that, ethically, he also represented Jeff as a band member. I kept excusing myself to the parking lot for cellphone conversations with Lisa, updating her on the latest proposal.

In the end we made the deal, they went back on the road, and Jeff died a little over a year later. I drove back to Nashville that night, stopping through my beloved Sewanee so I could stand for a few minutes in All Saints Chapel, my most liminal space, and feel not only the love of God but also the love of the woman I realized, in this very spot, I couldn't bear the thought of living without.

Later they complained about their bill; well, in fairness Jeff didn't. My feelings have been hurt to this day.

Anyway, enough of all that. Eight calls today, the first in about an hour. Not a celebrity in the lineup. Back to the quotidian plod of the law.

Commentaires