"In the afterlife

You could be headed for the serious strife

Now you make the scene all day

But tomorrow there'll be Hell to pay

People listen attentively I mean about future calamity I used to think the idea was obsolete Until I heard the old man stamping his feet."

-Hell, by the Squirrel Nut Zippers

Over a decade ago, I attended the funeral of an old acquaintance whose lifetime of fried chicken and sweet tea dramatically clogged shut one or more blood vessels leading to his heart. He was a devout Southern Baptist, so the funeral service was filled with images of the hereafter, some lovely and some less so. We were assured by an earnest young associate pastor that my friend had gone immediately to heaven, and right now was sitting on an oak branch over a river, fishing with Jesus himself.

I had not been to seminary yet at that point in my life, but was bemused by the confident specificity of the description. How in the hell would this guy know where Bobby is right now, if anywhere?

I don't feel particularly close to answering that question myself, but have to admit it hasn't seemed worth my time, even when I wore a collar and comforted the families of dying people in the ICU. I have, however, always been curious about where this notion came from, this idea of being immediately transported to eternal bliss or, for most it seems, eternal punishment?

That question is the subject of Bart Ehrman's new book, Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife. I have long been a fan of Ehrman, a lapsed Episcopalian-turned evangelical Protestant-turned agnostic. He teaches now at UNC Chapel Hill, and has a couple decades of pop scholarship embodied in books that cover topics ranging from the historical Jesus to the noncanonical scripture that was a part of the life and thinking of the early church, but now largely unknown to us.

Ehrman traces the history of the afterlife through early Judaism, which did not give it much thought except, as reflected in the Psalms, that it was not a great place to be. The pre-Christian era Jews did not consider the soul to be separate from the body, so at the end of life there was only the nothingness of Sheol.

That all changed with the arrival of Hellenism, which embraced a dualism that considered the soul separate from the spirit. Ironically, it was the Maccabees, those angry rebels who tossed off Greek rule two centuries before Jesus, who were infected by this idea, in part because they yearned for a just creation. As they were being tortured to death in defense of their faith, they described an eternal paradise that would await them, and punishment for their tormentors that would reflect the painful ordeal inflicted on the devout Jews.

But punishment was not eternal, there was no billion year fire bath waiting on the other side. Rather, the evil and unjust would be annihilated, punished once and sent into nothingness while the virtuous would live with God in paradise forever.

That was the view of Jesus, who described eternal fire, but didn't say the damned would stay there for all eternity. He analogized hell to the trash pit Gehenna just below Jerusalem--it was a place of odorous fire (and of child sacrifice in the old, old days), but the stuff burning there eventually just burned up. Paul, being a messianic Jew raised in the same tradition, seems to have thought likewise.

But what about Lazarus and the Beggar, the parable in which Luke described an afterlife of torment for the rich man who ignored the sore covered pauper at his doorstep? That was only recounted in Luke's gospel, and almost certainly an invention of the author to address conditions of early Christians some sixty years after Jesus's death.

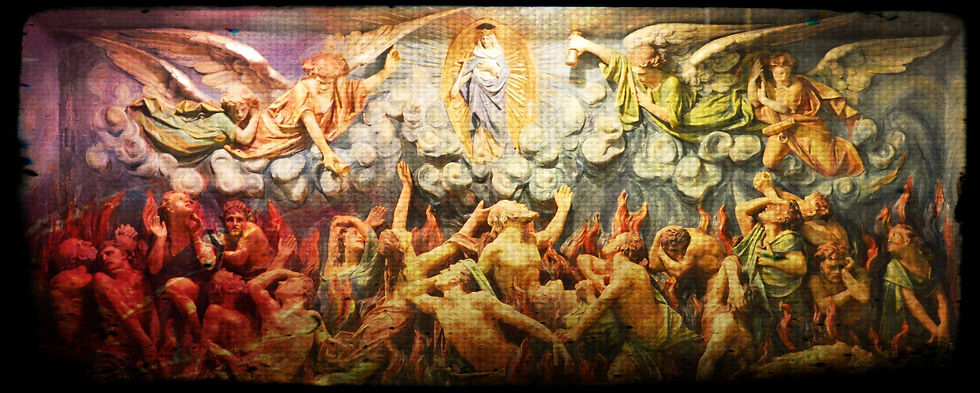

Indeed, it was the need to shape the behavior of unruly converts that seems to have given rise to this notion of eternal torment. The church fathers were, like Jesus, pretty vague about heaven--mansions, streets of gold, getting to see dead relatives. At the same time, they were specific about the torments of the hereafter.

"This is a place where eternally Fire is applied to the body Teeth are extruded and bones are ground Then baked into cakes which are passed around."

Okay, that's not a writing of the early church; it's the Squirrel Nut Zippers again. But it's not far from what was described in horrifying detail to our predecessors in the faith, with punishments sadistically designed and administered to mimic the sins that got one there, whether fornication, murder, abortion, theft, etc. Plenty of fire. Plenty of mutilation. All delivered by angels who appeared not to dislike their work, especially that most assiduously cruel of the pack, Satan himself.

Then there was the problem of when the Day of Judgment would occur for each of us. Again, early Judaism imagined a long, deep slumber until all would be judged. Not long before Jesus's time, they also developed the idea of a physical resurrection--remember that in Jewish thought there was no dualistic belief in the separation of body and soul. You can see the same thing in First Thessalonians, the oldest work in the New Testament.

Eventually, perhaps in a victory of marketing over theology, Christianity crept toward the belief that rather than lying in a dormant state until the Son of Man appeared in the clouds to judge all, we immediately at the moment of our death hurtled into a place of divine judgment, and most of us would get to start our punishment right away. That just felt better, more just, to a group of people being fed to lions by haughty public officials who seemed to be, well, getting away with it in this life. There needed to be reward right away. There needed to be punishment right away.

"Beauty, talent, fame, money, refinement Top skill and brain But all the things you try to hide Will be revealed on the other side."

Yep, SNZ again. Great song. You should look it up.

So by the third century, we'd gone from deep sleep until judgment and annihilation for the wicked, to immediate, eternal punishment. Or maybe eternal bliss for the few who made the cut. That's about where modern American evangelical thought stopped.

But in fact, the hereafter continued to evolve. Was punishment really eternal? Why would a just but merciful God create in his image a being he would then arrange to torture for a trillion years over an adulterous tryst at a Rotary convention? Isn't there a problem of proportionality?

And along comes Origen, one of our great, largely forgotten (outside of seminary, where his writings are a mandatory topic of discussion) church leaders and thinkers. Origen did not buy the idea of eternal punishment--he thought the purpose of damnation as it came to be understood in his time was to purify. He concluded that God would ultimately redeem and save all of humanity. Picture an eternal banquet at the end of the story, with Mother Theresa partying next to Pol Pot.

You can see how Purgatory morphed out of all this, a place for the kind of but not terribly bad to be cleansed by sometimes mild torture until they were summoned from above to enter the presence of God.

So, what to make of all this? Well for starters, treating the story of heaven and hell as an evidentiary matter that can be approached like any other (said the lawyer), it is pretty clear that what you hear being spouted from pulpits all over the world is our own creation. It is a fiction developed to scare or coax wavering believers into a set of behaviors that would benefit the tribe. Think family values, generosity to the poor, not murdering your neighbor and taking his stuff. All good things to be sure, but do we really need a children's story to embrace them?

Which is not to say there is no afterlife. Being alive and all, I'm not qualified to opine on that, and interestingly seminary didn't talk much about it. There was no class that trained us to describe the pleasures of heaven (if pleasure itself isn't a sin in one's world) or the pains of hell. Maybe if I'd gone to a different seminary that embraced fundamentalism it would have been different.

In the end, I guess I end up with Ehrman on this issue, who in turn points to Socrates's (or, more accurately Plato's) speech at the end of his trial in the Phaedo. Socrates has been sentenced to death for corrupting morals, and suggests death could mean one of two things, neither bad. On the one hand, if it is nothingness, we enter a dreamless sleep and are beyond suffering or pleasure. On the other, if it is "travel to a foreign land", that place would be populated, and presumably ruled (Plato's politics in the Republic seem to have seeped in here), by the best and the most just from all of human history. He looks forward to lunch with Homer or Hesiod. Either way, why worry?

Our church fathers, and their descendants right down to the Pat Robertsons of the world, have tried to answer that question in sociopathic detail. But if you sit down and take a long look at how their vision of eternal torture evolved, you realize they are all full of it. We would all sleep on a softer pillow, and likely live in a much better world, if that were more widely understood.

コメント