"You people of the South don't know what you are doing. This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization! You people speak so lightly of war; you don't know what you're talking about. War is a terrible thing! . . . You are bound to fail. Only in your spirit and determination are you prepared for war. In all else you are totally unprepared, with a bad cause to start with. At first you will make headway, but as your limited resources begin to fail, shut out from the markets of Europe as you will be, your cause will begin to wane. If your people will but stop and think, they must see in the end that you will surely fail."

Comments to Prof. David F. Boyd at the Louisiana State Seminary (24 December 1860), as quoted in The Civil War : A Book of Quotations (2004) by Robert Blaisdell. Also quoted in The Civil War: A Narrative (1986) by Shelby Foote, p. 58.

When I was a boy growing up in North Georgia, my Uncle Lehman sent me a birthday gift in a jewelry box. When I opened it, figuring I would find a watch or a tie clasp, I instead found three or four Minie balls and pieces of what was probably grapeshot. The note inside explained:

"These were dug from our family's farm outside Statesboro. Hopefully they were used to good effect against the Yankee invaders."

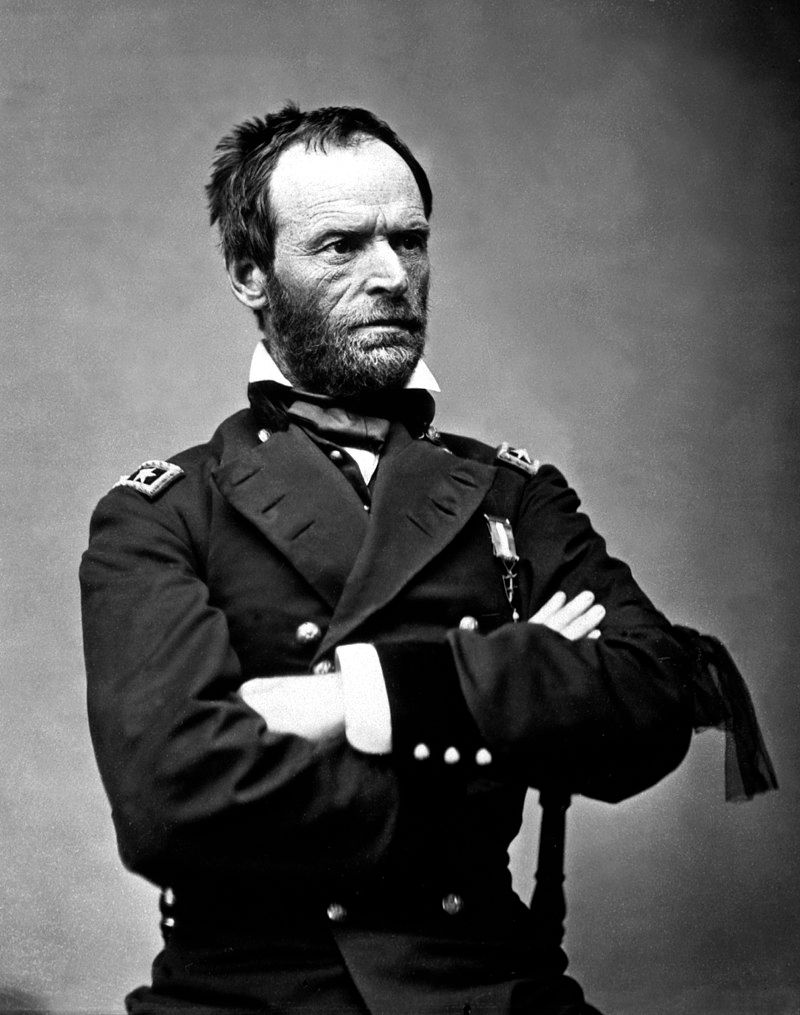

The invasion, the fall of Atlanta, and the March to the Sea still felt like fresh wounds then, almost exactly a century after those events were seared into the memory of Georgians. And the villain in the story, always, was William Tecumseh Sherman, the Jeremiah of total war who promised to "make Georgia howl."

The state would spend decades rebuilding, as if a vast hurricane had drifted like a sash from Rabun Gap to Tybee Light, destroying everything in its path. And Sherman's cruelty was blamed for it all, rather than Georgia's horrible decision to secede three years before.

But Sherman wasn't the maniacal brute to whom I was introduced in the Cobb County schools. He knew enough of war to hate it, and was forced to make an incredibly difficult decision in 1860 when Louisiana seceded from the Union while he was the superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary & Military Academy (later LSU). Sherman was an admired figure there, and he and his family had built a life in Louisiana over the year or two he'd been superintendent.

But Sherman's happy sojourn was short-lived. His neighbors went crazy, seceded from the Union, refused to accept the results of the election of 1860. Finding himself suddenly a foreigner in a country that was clamoring for war with the United States, Sherman left it all behind, packed up his family and moved back North. Before he left, he made the prescient observation that began this post to one of his faculty colleagues. Four agonizing years followed, during which he rose through the officer ranks, suffering a nervous breakdown along the way, and ultimately became the Union's most successful general, and the first modern general in the eyes of some historians.

Given what he lost and left behind when those around him put self-interest above country, in a deluded attempt to thwart the will of the majority and preserve an institution that relied on brute force and violence to enslave an entire race of people, it is unsurprising that he was not inclined to show much mercy when he returned to the South with 100,000 troops to put down the rebellion.

I find myself thinking of Billy Sherman this morning, after driving to work past a sea of Trump signs, flags, and bumper stickers. My neighbors daily declare their affinity for someone who has stated on the record that he will not respect the outcome of a popular election, and will fill a Supreme Court seat in record time while suggesting that same court will ultimately decide the election at his request. This is actually more insidious than the actions of Sherman's disloyal neighbors, in that we are seeing a virus take over the body politic of the republic rather than seceding from it, subverting its institutions and values in favor of a political minority that apparently will stop at nothing to maintain their privileged position.

Which raises the question, at a personal level, of what to do next. Peg and I have built a life here. I have spent nearly a quarter century establishing a law practice that is anchored in this place, and I feel a deep affection for its people, even the ones who are cheering on the coup. Do we, like Sherman, pull up stakes, shake the dust off our feet, and go try to start a new life in free America? Do we have an obligation to stay and play the role of the prophetic voice in the midst of all this madness? That carries a price, as well. I am already seeing its effect on my practice, to the extent I allow my views to slip out in public. And it's not like anything I say or do will change anyone's mind.

This is not where I wanted to find myself at 56 years old, but it's life. Billy Sherman started over rather than being complicit in what he saw as treason. Maybe that is the only principled answer.

But I already miss my chickens as I contemplate leaving them behind. Would it be possible to, like Diocletian, withdraw from public life and grow cabbages?

A lot to think about on a rainy morning.

Comments