“Winter is the time of promise because there is so little to do – or because you can now and then permit yourself the luxury of thinking so.”

– Stanley Crawford

"Good friends, let's to the fields ...

After a little walk, and by your pardon,

I think I'll sleep. There is no sweeter thing,

Nor fate more blessed than to sleep.

I am a dream out of a blessed sleep –

Let's walk, and hear the lark."

-Edgar Lee Masters

"Can't wait to read about whatever adventure you two go on this weekend," a coworker commented to P in the operating room this past Friday.

Well, they'll have to keep waiting, because there was no adventure. Friday afternoon found me just emerging from a couple days of the non-Covid crud, and no sooner did I start to rally than P was gripped with a more virulent version of the same thing. No fever, but nose running and hacking cough, coupled with extreme fatigue. All she wanted to do was sleep, and we listened to our bodies and did just that for most of the weekend.

P probably slept fourteen hours Saturday and Sunday, while I took advantage of the lack of decent football to curl up in one of the barrel chairs in the bar, or stretch out on the couch, and read a couple books. Of course, the latter scenario involved working through the text in fits and starts, as I followed my habit when reading reclined of falling asleep for a series of twenty minute micro-naps. I guess I was exhausted as well. It's been a long year, and these short, dim gray winter days (or late fall if you're particular about these things) seem to reach something deep within our evolved psyche and gently command us to rest. When I was young I'd fight that urge, even as the sun would set there on the far eastern edge of the central time zone, in Panama City, at 4:30 in the afternoon. I'd force myself to keep working until seven or so, as always, ignoring the seasons and rhythms of life around me.

No such denial this December, as we draw toward the solstice and I listen to my body when it feels time to nap.

So, what am I reading these days?

A few days ago I encountered a piece in the New York Review of Books about Spoon River Anthology by Edgar Lee Masters. The essay commented that most American high schoolers had been forced to read the series of poems at one time, which made me wince having never even heard of the book. Then I read on about Masters, a lawyer who hit it big after the book was published in 1915, quit his law practice (a partnership with Clarence Darrow), divorced his wife, and ran off to become a professional poet. He ended up dying broke--that poem at the beginning of this blog is on his headstone.

So for less than ten dollars, Amazon has filled this gap in my education.

There have been a handful of books that have knocked me back on my heels in my life, resonated and guided and spoken to the season in which they arrived. Marcus Aurelius's Meditations would be one of those, as I tried to find meaning in my then-recent experience in the Gulf War. A Place to Come To by Robert Penn Warren was another, as I was pondering leaving law for academia, and found myself traveling with Jed Tewksbury as he emerges from small town penury, then combat, to become a scholar, always haunted by the shameful death of his father who fell drunk under a wagon wheel while waving his own father's Confederate cavalry sword over his head in a late-night debauche. You can't get away from who you are, no matter how many degrees you accumulate.

Spoon River Anthology seems one of those books, a voice that illuminates my own life with its insights into small town society and what goes on just beneath the veneer. The book is a series of free form poems, each eponymously titled as the character speaks from the grave of the things he or she couldn't acknowledge until death laid bare the absurdity of it all. There are failed marriages, abortions, random accidents that forever change or perhaps end a life. The form is almost always tragedy and not comedy---there is no redeeming moment in the end, no happily ever after. These folks are just dead, and speaking of what really transpired in their lives.

Being a lawyer himself, Masters brings us several self-portraits of judges and attorneys, none very flattering but to someone with nearly twenty-five years in the law rather insightful.

There is the Circuit Judge:

TAKE note, passers-by, of the sharp erosions

Eaten in my head-stone by the wind and rain—

Almost as if an intangible Nemesis or hatred

Were marking scores against me,

But to destroy, and not preserve, my memory.

I in life was the Circuit Judge, a maker of notches,

Deciding cases on the points the lawyers scored,

Not on the right of the matter.

O wing and rain, leave my head-stone alone!

For worse than the anger of the wronged,

The curses of the poor,

Was to lie speechless, yet with vision clear,

Seeing that even Hod Putt, the murderer,

Hanged by my sentence,

Was innocent in soul compared with me.

This one, spoken by an insurance defense lawyer named John M. Church, was sort of a gut punch.

I WAS attorney for the “Q”

And the Indemnity Company which insured

The owners of the mine.

I pulled the wires with judge and jury,

And the upper courts, to beat the claims

Of the crippled, the widow and orphan,

And made a fortune thereat.

The bar association sang my praises

In a high-flown resolution.

And the floral tributes were many—

But the rats devoured my heart

And a snake made a nest in my skull!

A little too close to home, all that. I guess I tried to redeem myself with the whole religious adventure of the previous decade, but here I am back in the trenches with my rat-devoured heart.

Several of the poems bring us the same events, but from different perspectives that provide startling insight not into what happened, but rather the hearts and perceptions of those involved.

Take the situation described by Mrs. Charles Bliss:

REVEREND WILEY advised me not to divorce him

For the sake of the children,

And Judge Somers advised him the same.

So we stuck to the end of the path.

But two of the children thought he was right,

And two of the children thought I was right.

And the two who sided with him blamed me,

And the two who sided with me blamed him,

And they grieved for the one they sided with.

And all were torn with the guilt of judging,

And tortured in soul because they could not admire

Equally him and me.

Now every gardener knows that plants grown in cellars

Or under stones are twisted and yellow and weak.

And no mother would let her baby suck

Diseased milk from her breast.

Yet preachers and judges advise the raising of souls

Where there is no sunlight, but only twilight,

No warmth, but only dampness and cold—

Preachers and judges!

Reverend Wiley shows up a couple poems later, with a different take on the value of his advice:

I PREACHED four thousand sermons,

I conducted forty revivals,

And baptized many converts.

Yet no deed of mine

Shines brighter in the memory of the world,

And none is treasured more by me:

Look how I saved the Blisses from divorce,

And kept the children free from that disgrace,

To grow up into moral men and women,

Happy themselves, a credit to the village.

I suppose one reason these folks seem so real is that they were in fact real; Masters collected the stories of people in his hometown and his grandparents' hometown when he was growing up, changed the names slightly, and told their stories. The ones who recognized themselves, and apparently there were a few, were not flattered.

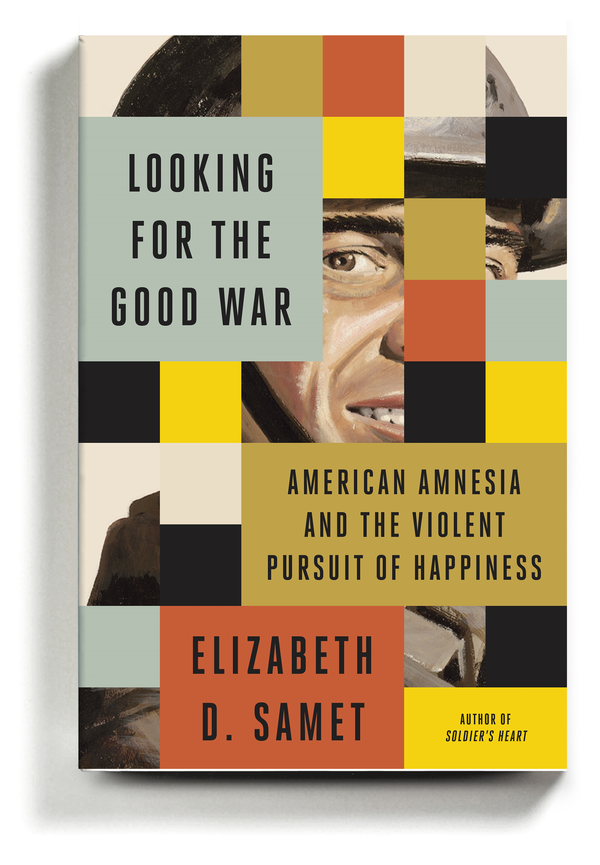

The other book that caught my eye and has engrossed me over this lazy weekend is Looking for the Good War: American Amnesia and the Violent Pursuit of Happiness by Elizabeth Samet, a professor of English at West Point.

This is my second book of the fall written by a West Point prof, the other being Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner's Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause, by Ty Seidule. Finding these thoughtful meditations on matters taken as bedrock truths that have formed the foundation of my own life, both written by teachers at the USMA, has left me questioning my decision not to attend a service academy when I had the chance. Maybe they really are training leaders there, although my own experience with ring knockers in the ranks was that they never really grew up, and seemed to see the world through narrow visors.

I digress.

Looking for the Good War so far (I haven't finished it yet) challenges the sentimental myth of the Second World War as a crusade with the whole country behind it, making sacrifices to save the world as our citizen soldiers uniformly behaved with valor and pluck. You know the narrative--it's the Stephen Ambrose/Tom Brokaw school of hagiography. Samet takes issue with all that, not only because it turns a complicated moment of our national past into a children's story, but also because this airbrushing has led us on an impossible quest to replicate that moment of national unity and purpose in a series of ill-conceived military adventures that have left us with piles of bills and bodies and not much else to show for those endeavors.

I just finished reading her discussion of the outsized role the Gulf War played in giving new life to our national obsession with military adventure. She observes that Korea and Vietnam had brought the country to reconsider war as an instrument of policy, domestic and foreign, but the rapid and relatively bloodless (for us) defeat of a tyrant and liberation of a captive nation brought us right back to the wrong lessons learned in 1941-45, redeemed the humiliation of Vietnam, and renewed our faith in the efficacy of our armed forces. All that led, perhaps inevitably, to the fraudulent blunder of Iraq in 2003, and the myopia of the twenty-year war in Afghanistan and the chaotic collapse of that society when we left.

Not long after I came home from Saudi Arabia, I remember musing over home brews with my buddy Fasty, a squadron mate during the war, that the country had learned the wrong lesson from what had just happened. We made it look too easy--it wasn't--and Americans would show that much less reluctance and circumspection the next time an opportunity for combat presented itself. This seems to be Samet's point, that we reshape our memories of wars, especially seemingly successful ones, and create a myth that guides us Siren-like onto the shoals of the next military disaster. That this habit can traces its origins all the way back to Thucydides, and Homer before him, leads one to see this as a facet of human nature, and leaves little room for optimism that we'll overcome our tendency toward delusion when it comes to war.

It is the blessing of winter, of short days and frigid nights, that we have time to read and to ponder on these things. If we have evolved to live on an earth that moves with these rhythms and cycles of life, we must learn to move with them, and to recognize when it's time to rest.

But for now, I'll work a little and await P's arrival in two or three hours for our trip to Buffalo. I was supposed to be picking a jury in Panama City in about an hour, but the case mercifully resolved and we decided to take the opportunity to travel to Buffalo today for the James Taylor-Jackson Browne concert there tonight. More on that adventure when we get home.

Comments