"People die', she says. 'People tear down houses. But furniture, fine, beautiful furniture, it just goes on and on, surviving everything.' She says, 'Armoires are the cockroaches of our culture.' "

-Chuck Palahniuk, Lullaby

A pretty morning out there in the Southern Tier.

Doesn't look eighteen degrees, does it? Well it is. Or was. My computer says we're up to 20 now. Things are looking up.

All this cold left us worrying about Slane in the predawn darkness. You see, Slane dutifully sleeps on top of Peg's head, just to her left, most nights. When he doesn't he's usually down by the fireplace, but in either case we hear from him around five each morning when I'm here, mournfully yowling for his breakfast like a mullah calling the faithful to morning prayer.

But this morning he didn't, which caused some consternation in the master bedroom.

Well, consternation for me anyway. Peg has a gift for coming back to bed from the bathroom at 4:30 and falling blissfully, snoringly asleep. On weekends it can last until after eight. If early morning slumber were an Olympic sport, Peg would droop under the weight of her medals.

So this particular morning she expressed concern over Slane's absence, conjectured that maybe he'd frozen to death out there in the darkness, then fell deeply asleep.

Which left me to my predawn lucidity. For most of my professional life this has been a time reserved to lie there and worry about deadlines and court filings and whatever else populates my life as a lawyer, but this morning I just felt that deceptive clear-headedness one sometimes encounters in the silence and the dark. I say "deceptive" because often, once I'm fully present and have finished a double espresso, all those insights turn to dust in the light of the morning.

But that didn't happen here. First, I pondered why the autopilot in the Columbia won't fly an intercept heading to final approach when I've loaded the approach as "vectors to final" on the control panel, and I activate the approach a few miles out from the final approach fix. Well, if you're in "nav" mode, or even "approach", as soon as you activate the approach the plane will fly to the next fix on the approach, not whatever heading you dial up. Simple enough, but the same thing happens when you activate the approach in "heading" mode, in that Hal the Computer thinks when you activate the approach you're off vectors. Next time I'll press the "HDG" button on the panel after the approach goes active, and see if that holds me on my last vector to final.

I know you care deeply about this, but there's more.

The fairings and leading edges of the wings have started to shed their paint lately, as if it's been sanded off. It's unsightly, and would invite corrosion but for the fact that this plane is all composite. But why has this begun to happen, sixteen years after it rolled off the assembly line?

I've seen this before during my time flying the F-15. A squadron mate of mine in the Fightin' Eagles, Lips Ballinger, was chasing an F-14 in a dissimilar air combat training mission off the Virginia coast. He was carrying a centerline tank, which limited the jet to 660 knots indicated. Apparently Lips exceeded the placarded limit, and upon returning to Langley was called out by the maintenance troops when they found that the sea air at that speed had sanded all of the paint off the nose of the tank.

I do tend to fly my enroute descents pretty aggressively, leaving the power up and accelerating to the edge of the yellow arc on the airspeed indicator. But the plane is designed to fly at that speed, and the peeling thing never happened before. What's going on here?

Well, around 5:05 a.m. I developed a theory. Lately the Columbia has been a beast to start; it runs fine once it runs, but getting there involves a lot more throttle than should be required. This means that once it coughs to life, it immediately digs in and the RPM surges to maybe 1800, rather than 900 as designed. And that angry prop is taking all the dust and weeds and gravel, and throwing them backwards at hurricane force. If we're on a clean ramp, like KELM, it's not a serious problem. But Perry-Foley has one of the worst maintained ramps you'll see, all weedy and dirty. Basically, every time I start there I sand the leading edges of the plane. Mystery solved, perhaps.

I need to get Doug the mechanic to address this, lest the plane lose its aesthetic appeal.

Then I drifted to thoughts of law practice management, and how we need to revisit the paradigms in which we were raised. When I was thirty, partners my age tended to bill less, but derived their value from bringing work in the door based on their reputation, and farming it out to the younger troops. We'd "feed the beast", as my old partner Bob Hughes used to say, keeping associates busy doing research and drafting motions. Then we'd pay them about a third of what we collected for their work, "leverage" in the lingo of the profession. A hard-working young lawyer paid her dues, and after a few years of funding partners' new boats and alimony payments, herself became a partner leveraging some young associate to fund her own alimony.

So here I am, with more work than I can say grace over, and . . . no one to take on the heavy lifting. We're partner heavy, like most firms, and my partners are as busy as I am. We engage in turf wars over associates, who no longer serve what amounts to an apprenticeship then a long career at a single firm; most don't last five years, flitting from firm to firm and wondering why their career hasn't provided the standard of living they observe in their elders.

But rather than grousing over all that like a petulant old man, maybe I need to embrace it. The thing I thought brought value to my presence in the firm really has no value at all, in that there's no more leverage and no excess capacity to take on more work for the firm. Clients don't want to pay $250 an hour for a trainee--they hired me, not the firm. That being so, our business model needs to shift to making sure that our partners are at the top of their field, and that we have partners trained in multiple areas of the law so we don't have to refer a matter to another firm because we don't have someone conversant in, say, eminent domain. And we need to take some of the money we're not spending on junior lawyers, and spend it on maintaining the technology we need to compete with the big firms in this era of electronic discovery and 50,000 page data dumps.

In sum, we need to worry about practicing at the highest level, in multiple areas tailored to the sort of mischief one encounters in the panhandle of Florida. It's a totally different model than the one in which we grew up, but times change.

This is what happens when Slane isn't around to break my train of thought with his incessant begging in the wee small hours.

Where was he? As soon as I crawled out of bed to make P her coffee, I turned on the back porch light and peered into the frozen darkness. Nothing.

I called to Slane, and told him Dean was going to get his breakfast. Silence.

I checked the front porch, although he's never there when he returns from his evening adventures. He wasn't there, either.

By this point Dean followed me attempting his own brand of plaintive whining, reminding me that he'd be perfectly happy to enjoy his breakfast without the usual interruption when Slane pushes him out of the way to feast on Dean's breakfast plate.

So I fed Dean, and went about my chores. Then I noticed Dean, having finished his breakfast, had made his way to the mud room, where he kept looking back at me and pacing around, agitated.

I followed him into the room, and encountered the still, small voice. A tiny meow.

I checked outside the mud room door. No Slane. I checked the basement door, thinking maybe I was hearing him below the floor. Nada.

Finally, I opened the door to the armoire, and out jumped Slane. He'd apparently crawled into the cabinet when Peg came home last night and put away her coat. The antique is so solidly built we couldn't hear him unless we were standing right next to its heavy wood doors. I'm glad he didn't suffocate in there.

The armoire itself is a story.

We purchased it during our wine-soaked bidding spree at the online auction of Amo Houghton's estate. A friend in the neighborhood saw it shortly after the armoire arrived at Tara, and waxed nostalgic about how he and his friends played hide-and-go-seek in the old piece of furniture when it lived in Amo's basement in the 1960s.

But, upon closer inspection, it wasn't Amo's armoire at all. It was his grandfather's.

The clue that led me there was the tag inside one of the three chambers, from a store in London.

You see, Amo's middle initial wasn't "B"; in fact, as near as I can tell, he didn't have a middle initial at all. And he was never stationed in London.

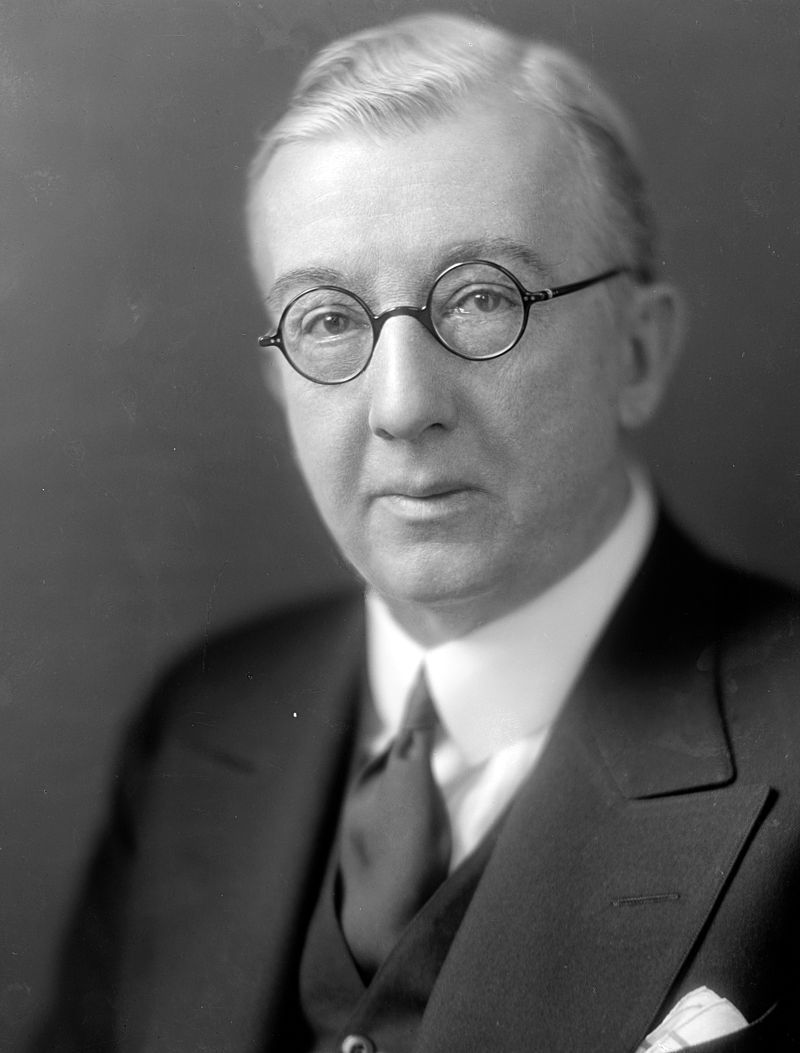

But his grandfather, Alanson B. Houghton, had been.

Alanson had served as a congressman, then our ambassador to the Weimar Republic, then our ambassador to Great Britain from 1925 to 1929. It was likely during this window that he purchased the armoire that now sits in our mud room, housing the coats of this household of plebeians and the occasional bag of Traeger pellets I want to keep dry. He's buried up on the hill with the rest of the Houghtons. Maybe P and I will walk up there tonight and assure him we're taking good care of his wardrobe.

コメント